Immigration has been an important element of U.S. economic and cultural vitality since the country’s founding. This timeline outlines the evolution of U.S. immigration policy after World War II.

As the Cold War deepens, the U.S. government consolidates its immigration and naturalization laws into one comprehensive federal policy. The McCarran-Walter Act ends policies stemming from the late nineteenth century designed to exclude Asian immigrants. However, the bill upholds the ethnicity-based quota system for new immigrants that favored white Europeans, revising limitations to admit one-sixth of 1 percent of each group already in the United States. President Harry Truman vetoes the bill, citing discrimination against Asian immigrants and decrying the “absurdity, the cruelty of carrying over into this year of 1952 the isolationist limitations of our 1924 law.” Congress overrides him to pass it.

The postwar period causes a swell of illegal immigration to the United States from Mexico, with an estimated three million undocumented Mexicans in the country working mostly in agricultural jobs at significantly lower wages than what American workers receive. Under growing public pressure to act, the Immigration and Naturalization Service under President Dwight D. Eisenhower enacts a nationwide sweep of undocumented Mexican immigrants in the southwestern United States. The sweep, officially termed “Operation Wetback,” authorizes 1,075 Border Patrol agents, along with local law enforcement, to target barrios in California, Arizona, and Texas.

Hungary’s failed revolt against Soviet control triggers an outpouring of refugees. The Eisenhower administration uses a provision in the McCarran-Walter immigration act authorizing the admission of aliens on a temporary basis under emergency conditions. Eisenhower employs parole powers—presidential authority to take unilateral action in emergencies—included in the immigration act to admit around thirty thousand Hungarian refugees. By 1960, more than two hundred thousand Hungarian immigrants are accepted into the country, and Eisenhower’s use of parole powers marks a precedent used in later decades to grant tens of thousands of refugees from around the world asylum in the United States.

Fidel Castro and his guerrilla forces overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba in January 1959 and set up a new communist order, resulting in a mass exodus of Cubans to the United States as political refugees. The first wave includes political supporters of Batista, as well as members of Cuba’s elite and middle class, who largely settle in Florida’s Miami-Dade County. The United States eventually enacts the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act to allow permanent resident status to Cuban refugees who arrive after 1959. About one million Cubans emigrate to the United States between 1959 and 1990.

Amid mounting pressure from labor activists and welfare organizations, the U.S. government lets its Mexican guest worker program expire after twenty-two years. The Bracero program, instituted in a bilateral agreement in 1942 amid anticipation of a labor shortage in World War II, gave contracts to Mexican workers to be employed in the U.S. agricultural sector. During its operation, about 4.5 million contracts were signed for workers to come to the United States. Although the program stipulates that braceros are entitled to certain provisions—including equal wages to native workers, free housing, affordable meals, and insurance—these rules are broken by many employers. Many of the farm workers are reported to receive a fraction of the wages of American laborers. Lee G. Williams, the last director of the program under the Department of Labor, refers to the system as “legalized slavery.” The end of the Bracero program results in an acceleration of illegal immigration across the border.

In the midst of the civil rights movement, the government shifts federal immigration legislation away from the quota system and 1920s standards, deemed by President Lyndon B. Johnson as “un-American in the highest sense.” The 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act [PDF] instead sets up a system of preferences, placing an emphasis on family reunification. President Johnson, signing the bill at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, declares that the legislation “is not a revolutionary bill and does not affect the lives of millions.” However, the bill—through the family preference that allows naturalized U.S. citizens to sponsor relatives to emigrate to the country—sets the course for dramatically altering the demographics of the country.

In response to rising calls to assist Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union, Congress moves to enact a human rights-oriented amendment to the Trade Act of 1974. The Jackson-Vanik amendment requires non-market economies to provide free emigration to trade with the United States under “favored nation” status. The amendment receives strong support in Congress and eventually allows for the emigration of more than five hundred thousand people—many Soviet Jews, Christians, and Catholics—to the United States until its repeal in 2012.

Southeast Asia is racked with turmoil in the 1970s as the Vietnam War winds down, the Khmer Rouge seizes control in Cambodia, and Laos falls under the control of the Pathet Lao. After Saigon is captured by the People’s Army of Vietnam, the Gerald Ford administration enacts the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act [PDF] to help about 130,000 Southeast Asian refugees. The move receives broad support among civil rights advocates, religious groups, and organized labor, and the number of Southeast Asian “boat people” immigrating to the United States swells by the early 1980s. This new influx, largely brought in by executive parole power, prompts the government to consider a broad overhaul of the nation’s refugee admission system.

As Southeast Asian refugee numbers mushroom, Congress crafts a bill to systematize U.S. refugee policy, which has relied on ad hoc use of presidential parole power. President Jimmy Carter signs the Refugee Act of 1980, an amendment to the 1965 immigration act that raises the limit of refugee visas granted from 17,500 to 50,000 per year, exempting these numbers from the overall immigration ceiling, and formally establishes the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Additionally, the law modifies the definition of “refugee” to give it more of a universal scope and make it consistent with the UN Refugee Convention, a move that addresses long-standing criticism of the United States’ preference for admitting refugees from communist countries.

Congress approves the Immigration Reform and Control Act to address the estimated three to five million undocumented immigrants in the country. The policy officially mandates employers to affirm the immigration status of their employees and outlaws the practice of knowingly hiring undocumented immigrants, although the administration’s enforcement of penalties remains lax. Additionally, the law grants legal status for certain seasonal workers and unauthorized immigrants who arrived in the United States before 1982. However, the IRCA’s most significant legacy is its provision to give undocumented immigrants arriving before 1982 the opportunity to apply for permanent residence before May 1988, a measure that eventually grants legal status to 3 million people, of which 2.3 million are Mexicans. Illegal immigration continues to flow after the IRCA’s passage.

Looking to focus on legal immigration pathways, President George H. W. Bush signs the Immigration Act of 1990, which expands the 1965 act to allow for an increase in the overall number of immigrant visas granted. While family reunification-based immigration remains a preferential category, priority is also extended to high-skilled and educated workers. The act creates five categories of employment-based (EB) visas as well as the temporary H1B visa for college-educated foreigners, and sets a cap on the number of unskilled workers emigrating into the country. The law also creates a diversity lottery to distribute visas among those from underrepresented countries. After the legislation is passed, the number of annual immigrant visas granted spikes from five hundred thousand to seven hundred thousand.

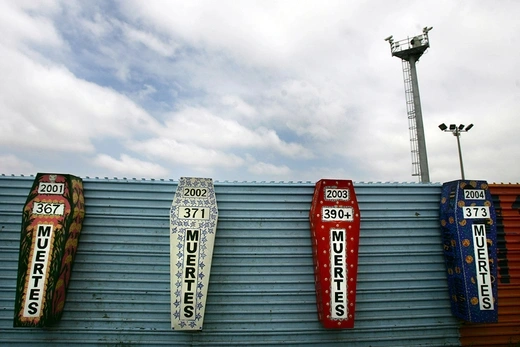

Bill Clinton’s administration launches Operation Gatekeeper to stave off illegal immigration across the border between San Diego and Tijuana, known for unauthorized border crossings from Mexico. Clinton doubles the number of Border Patrol agents along the southwestern border and authorizes $50 million* to build a fourteen-mile security fence, shifting unauthorized crossings eastward toward deserts and mountains. Shortly after its launch, the government declares it a success, but critics denounce it as a “militarization” of the border, and human rights groups connect it with the deaths of more than five thousand people who attempt to cross the more treacherous eastern terrain in California and Arizona over the next fifteen years.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union results in a loss of Soviet economic support to Cuba, resulting in a spike in the number of Cubans fleeing to the United States in the early 1990s. In 1994, Fidel Castro threatens to allow for a mass exodus if Washington does not take action against the illegal boat departures from Cuba. Both countries sign migration accords in 1994 and 1995 stating that the U.S. Coast Guard would no longer allow Cuban migrants intercepted at sea and without credible asylum claims; however, those who made it to U.S. soil would usually be allowed a path to citizenship. The policy is highlighted during the 1999 case of five-year-old Elian Gonzalez, found in coastal waters after his mother and ten others die attempting to cross to the United States. Relatives in Miami are denied custody of Gonzalez and he is subsequently returned to his father in Cuba.

To address the issue of the estimated 2.1 million minors who are brought illegally to the United States as children, Congress introduces the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, a policy that would carve out a path to citizenship for these young immigrants if they meet certain conditions, including graduating from a U.S. high school or serving two years in the military. The act goes through several revisions and languishes in Congress through the next decade, prompting states to enact their own versions of the DREAM Act to provide in-state tuition for these immigrants. In 2012, President Obama announces a deferred action program that bars this group of immigrants from deportation, and pledges to make the DREAM Act a part of comprehensive immigration reform.

In response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Congress passes the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which overhauls the organization of the federal government’s immigration functions. The act dissolves the Immigration and Naturalization Service and creates the Department of Homeland Security, which overtakes all immigration matters. DHS splits immigration services to divide enforcement functions—handled by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency—from naturalization and visa functions. The George W. Bush administration makes border security a top priority, strengthening screening and security measures at airports, allowing agents to more easily detain and deport immigrants with suspected ties to terrorism, and instituting more stringent visa application procedures. The government also enacts a program—suspended in 2011—requiring men from predominantly Muslim countries to pre-register and undergo additional screenings while traveling to and from the United States.